The gleaming badge presented to Peggie Wicks last month was long overdue. The great-grandmother had waited 63 years to receive official recognition from the Government for her unremitting toil in the darkest days of the Second World War.

Then, just three weeks after finally being honoured alongside a diminishing band of survivors from the Women’s Land Army (WLA), Peggie died at her Cheam retirement home, aged 83.

Her relatives are convinced that her passing, on August 30, came at the moment the long-deserved victory completed her life.

They are now planting an oak tree in Richmond Park as a fitting tribute to her efforts chopping them down to keep the war machine supplied.

The tree, and its attendant plaque, will ensure the memory of the forgotten Land Girls is kept alive - in one corner of the country at least.

Backbreaking efforts by representatives of the WLA had saved an embattled nation from starvation through two world wars.

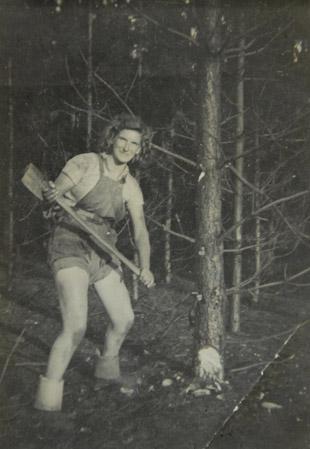

Clad in a uniform of brown woolen breeches, a brown felt hat and a green jumper and tie, the Land Girls and Lumberjills were often depicted smiling as they worked in sunshine.

But the popular image masked a grim reality of gruelling manual labour often undertaken by homesick urban recruits billeted in remote lodges or primitive hostels.

At their peak in 1943, 84,000 members felled forests, operated saw mills and ploughed fields while men were away on duty.

They also had to tend livestock, sow seeds, harvest crops and maintain tractors miles from family and friends, and with little formal training.

Conditions were unforgiving. As well as being pitch forked into hostile communities, the women complained about having to work through torrential rain when prisoners of war would typically be led to shelter.

Peggie’s eldest daughter Brenda, 61, said: “Peggy was drafted in to become a ‘ganger’ in the Timber Corps section of the Land Army, in charge of some 20 young ladies who soon became friends, being moved across the country to fell the trees that would be used for pit props, mainly in the coal mines and Bailey bridges for the troops.

“It was a very demanding and tiring job, and Peggy recalled one day when she failed to appear for work, her hands blistered and stripped of skin from pine trees.”

It was not always so torturous, however. The 1998 film Land Girls, based on Angela Huth’s exhaustively-researched novel, portrayed the more sybaritic existence of three recruits posted to a Dorset farm.

Derided for over-glamourising the exploits of wartime women, it still seems to have some echoes with Peggie’s experience.

Eric, 54, the youngest of her five children, says: “Travelling from Elvedon in Norfolk to Robertsbridge in Kent, to Derwent Water and Snake Pass in Derbyshire, the Land Army were a sight for sore eyes, and often flaunted the curfew time of 9pm on their days off.

“Peggy was caught more than once, finally being stripped of her role as ‘Ganger’ and would be demoted to private and fined the sum of two shillings and sixpence from her wage of 12 /6. Her father was also called to restore order to his daughter.

“While stationed at Newark in Lincolnshire, Peggy worked alongside many Italian PoWs and Danish seamen who helped along after fleeing their country, and near Macclesfield, after the forest had been cleared, the valley was flooded to create a dam which would be a great source of power for the war effort.”

Despite playing a vital role in Britain’s ultimate victory, the woman never received medals because Winston Churchill decreed their Army was a branch of industry, rather than a wing of the services. They were almost alone among those who contributed to the war effort in missing out.

It took the British Women’s Land Army Society decades of campaigning to win them formal acknowledgement for the first time last summer.

Announcing the awarding of commemorative badges, Environment Secretary Hilary Benn said the work women did was “a story from our history that must be told again and again.”

'It is absolutely right that we at last recognise the selfless efforts these women made to support the nation through the dark days of World Wars I and II. This badge is a fitting way to pay tribute to their determination, courage and spirit in the face of adversity.”

Hilda Gibson, 84, had carried out pest control on Lincolnshire farms and then on a poultry farm in Norfolk while serving between 1944 and 1946.

She said: “The whole experience has stuck with me ever since. I think it was a really good idea to create these awards. Everyone had to do their bit during the war and serving my country in its hour of need was a privilege. To serve one’s country in its greatest hour of need, in whatever capacity, for me, remains memorable.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here