For nearly 80 years after its creation, today’s Wimbledon Society took its name from a man who was never really associated with Wimbledon at all, although he paid a few visits.

Known first as the John Evelyn Club and then from 1949-82, the John Evelyn Society, this was actually a tribute to diarist and nature lover John Evelyn (1620-1706), who died 307 years ago this week on 27 February 1706 and was buried near his home in Wotton, Surrey.

Just before local resident Richardson Evans founded the Wimbledon Society in 1903 as a focus for those keen to preserve the area’s natural beauty and cultural heritage, he sent a long letter to 300 of his neighbours proposing the establishment of a John Evelyn Club.

He wrote: “I know of no other character in English history who showed so delicate a love of nature, such cultivated taste in art and such genial familiarity with the ways of men.”

At the time, Evans expected the Wimbledon club to be the first of a network of similar bodies elsewhere, all using the John Evelyn name to help maintain their own areas’ attractions.

It never happened, which was essentially why the name was eventually dropped in 1982.

Although Evelyn never lived in Wimbledon, he visited what was then a small Surrey village four times. His first trip on 17 February 1662 was as the guest of the Earl of Bristol who had recently bought the Wimbledon Manor House from Queen Henrietta Maria, widow of King Charles I. In his diary Evelyn says this visit was to help modernize the garden. He wrote: “It is a delicious place for Prospect and the thicketts but the soile cold and weeping clay.” Not very promising perhaps.

He didn’t return for another 13 years, calling one day again in August 1675. The following July he seems only to have met the Earl’s wife, Countess Anne, on his third visit and by the time he returned for the last time in February 1678 the Earl of Bristol had died and his widow had sold the Wimbledon Manor House to the Earl of Danby, Lord Treasurer.

This time, Evelyn was one of a party including the new owner’s daughters and they all surveyed the gardens and alterations to the house before leaving late at night. In January 1679 Evelyn was a guest of Bristol’s widow once again but this time at her new home in Chelsea. He seems never to have returned to Wimbledon.

He nevertheless represented many of the same ideals as today’s Society. Despite being the second son of a gunpowder manufacturer, he dedicated his life to intellectual pursuits, writing books on subjects ranging from theology, numismatics and politics, to horticulture, architecture and vegetarianism. He also mixed in impressive circles and included the architect Sir Christopher Wren, scientist Robert Boyle and fellow diarist Samuel Pepys among his friends.

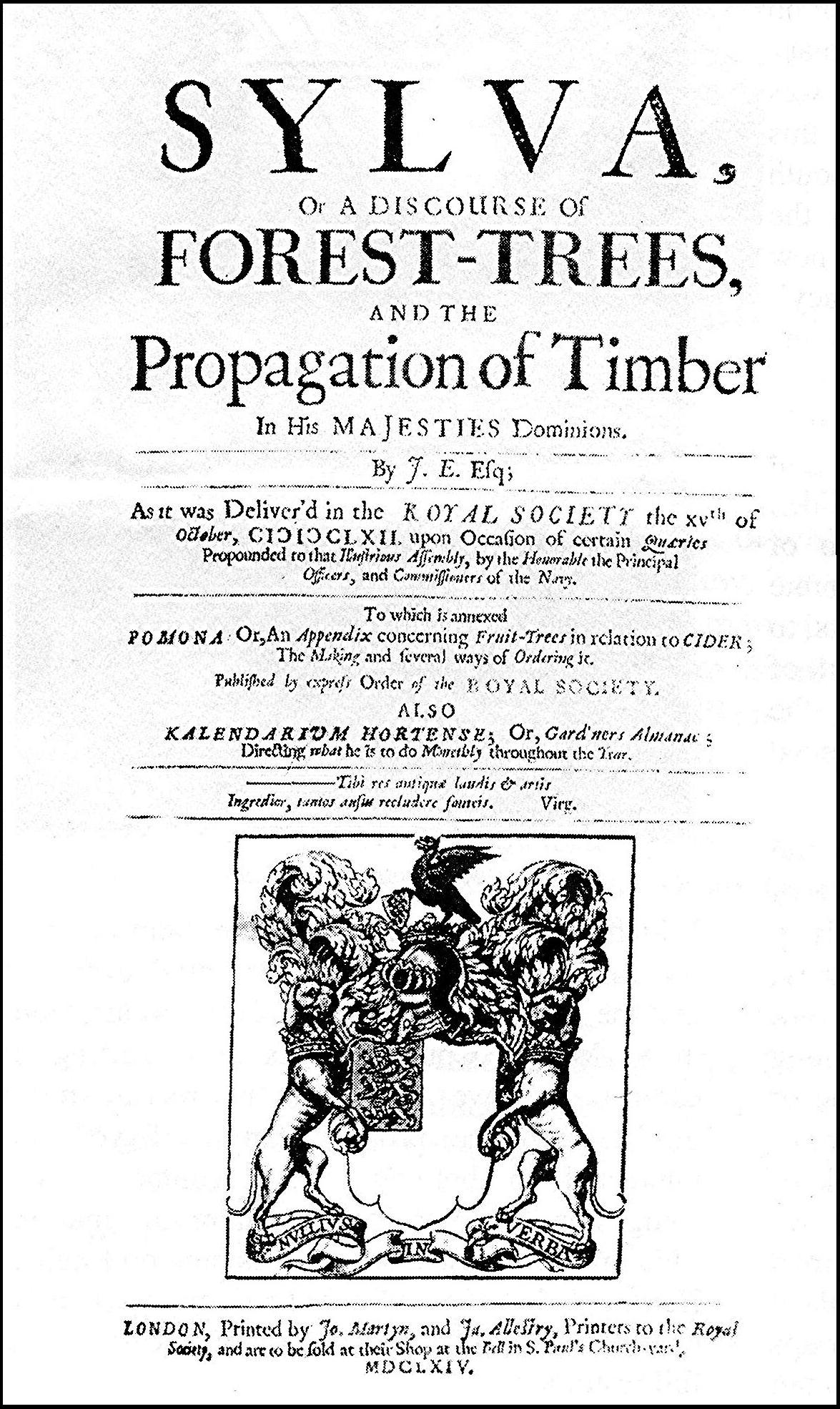

A founder of the Royal Society in 1660, Evelyn’s book on the growing problem of air pollution in London was published soon afterwards and in 1664 was followed by a highly influential treatise on forest trees and their propagation.

Entitled 'Sylva' with a sub-heading 'The Kalendarium Hortense Or Gard’ners Almanac', this was a treasure trove of advice to landowners on planting trees to provide timber for England's rapidly growing Navy.

Later editions appeared in 1670 and 1679, with the fourth published in 1706 just after his death. The Museum of Wimbledon at 22 Ridgway has a bound copy left by Richardson Evans himself.

Evelyn’s love of trees and the natural environment was always evident. His family home, Wotton House in Dorking, now a hotel and conference centre, still stands in the Italianate garden he designed himself on returning from ten years travelling in continental Europe.

But he only inherited that house from his brother late in life and for many years he had lived with his family at Sayes Court, a property near Deptford (then in Kent) where he transformed the gardens.

There too he happened to become the landlord of the man later considered England’s finest wood carver, Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721). In the 1670s, Gibbons rented a cottage in the grounds of Sayes Court and Evelyn introduced him to Sir Christopher Wren who in turn introduced him to King Charles II. Gibbons was then commissioned to produce work still found today at Windsor Castle.

As a conservationist centuries before the word was known, John Evelyn was horrified to see what vandalism could mean when brought too close to home. In 1698 King William III borrowed Sayes Court from him as a temporary location to host Russian Tsar Peter the Great and his court, who were visiting London to learn about shipbuilding at the nearby Deptford shipyard. The King had it specially furnished but hosting Peter was far from great.

For three months the Russian proceeded to wreck both house and grounds, painfully destroying a much treasured holly hedge by riding through it on a wheelbarrow. Evelyn got £150 in compensation from the Treasury after Sir Christopher Wren, then the King’s Surveyor, and his gardener, Mr London, examined the destruction.

But it was nature rather than a malign visitor that caused the most damage at Evelyn’s final home at Wotton. In his last edition of Sylva, he mentions that more than 1000 trees had been destroyed by the great storm of 1703 within sight of the house (See Heritage story 30 November 2012).

The Wimbledon Society is working with the Wimbledon Guardian to ensure that you, the readers, can share the fascinating discoveries that continue to emerge about our local heritage.

For more information, visit wimbledonsociety.org.uk and www.wimbledonmuseum.org.uk.

Click here for more fascinating articles about Wimbledon's heritage

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here